Issue Date: August 27, 2012

Diagnosing Opportunity

Keywords: diagnostics, scientific instruments, health care, medical treatment, drugs

Whether the new U.S. health care law survives after the November elections or not, the pressure is on to find ways to limit the growth of medical costs. One way to do that is to harness advances in in vitro diagnostics so that doctors can know with greater certainty what they are treating and whether a course of treatment is likely to benefit a patient.

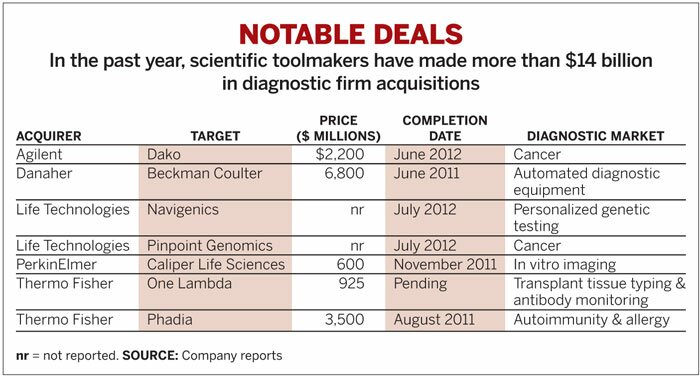

And so scientific instrument makers, which for years have enabled research on new drugs, increasingly see a role for themselves in diagnostics used by physicians to help choose those drugs at the point of care. In recent months, the biggest instrument makers, among them Thermo Fisher Scientific, Agilent Technologies, and Life Technologies, have spent more than $14 billion to acquire players in the diagnostics market as they jockey for advantaged positions in the increasingly competitive fray.

Just last month, Thermo Fisher, the world’s second-largest scientific instrument maker according to C&EN’s annual ranking (C&EN, April 30, page 14), agreed to buy the transplant diagnostics firm One Lambda for $925 million. The deal adds $182 million in sales from tissue typing and antibody monitoring tests to Thermo Fisher’s year-old specialty diagnostics division. The division was formed after the instrument company’s $3.5 billion purchase of allergy and autoimmunity diagnostics maker Phadia.

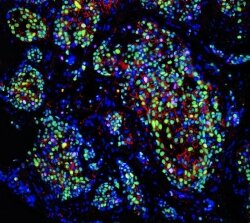

In June, Agilent, the number-three instrument maker, completed its largest-ever acquisition: the $2.2 billion purchase of cancer diagnostics firm Dako. The deal turns Agilent into a provider of antibodies, reagents, scientific instruments, and software to pathology labs. Dako had annual sales of about $340 million.

The fourth-largest instrumentation company, Life Technologies, also has its eye on the diagnostics market. In mid-July, the firm bought Navigenics, a personalized genetics testing company, as the first step in building a molecular diagnostics business. A week later, Life Technologies acquired Pinpoint Genomics, a cancer testing lab that has developed a polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based assay for non-small-cell lung cancer that uses Life Technologies’ qPCR platform.

Industrial products conglomerate Danaher snagged the number-one spot in C&EN’s instrumentation company ranking after its $6.8 billion acquisition of Beckman Coulter in June 2011. The move expanded its presence in both drug discovery equipment and diagnostics. Of the top five instrumentation firms, only number-five Shimadzu has stuck largely with its traditional scientific instrument focus.

What the instrument makers hope to do is profit from advances in patient tests that give very specific results. Older style commodity diagnostics such as blood chemistry and blood typing tests provide “general indicators that something is amiss,” explains Harry Glorikian, managing partner of consulting firm Scientia Advisors. “They’re like the engine light going on in a car—they don’t give much direction.”

Diagnostic tests developed in recent years through advances in genomics and proteomics, and enabled by improved electronics and bioinformatics, are directive, according to Glorikian. “They drive what the clinician does next and are like the oil light going on in a car,” he says.

Many of the latest diagnostic tests don’t depend on a physician’s interpretation, Glorikian points out. Instead, the tests can identify a specific disease or indicate whether a certain type of chemotherapy is working. Others, known as companion diagnostics (C&EN, July 23, page 10), are based on identifying biomarkers and can predict whether a course of treatment is likely to be effective.

Among the latest diagnostics to receive Food & Drug Administration approval is a test from assay technology and equipment maker Qiagen to help physicians determine whether a colorectal cancer patient may benefit from treatment with the monoclonal antibody cetuximab, also known as Erbitux. The PCR-based test screens for the presence of KRAS mutations in tumor cells that affect a patient’s susceptibility to treatment.

Qiagen, which ranks number 24 on C&EN’s instrumentation list, says it expects annual U.S. sales of the colorectal cancer test to reach $20 million. Use of the test could save the U.S. health care system $600 million annually, the firm says, by avoiding use of cetuximab when it won’t be effective.

Diagnostics are a logical extension of scientific toolmakers’ existing business, notes stock analyst Dan L. Leonard of investment firm Leerink Swann. Instrument makers can benefit from the sales of test kits as well as the equipment used to administer them.

However, Lawrence Schmid, president of consulting firm Strategic Directions, isn’t buying the business logic of the push into diagnostics. “The move by big instrument makers to buy diagnostics firms is crazy,” Schmid says. As he sees it, instrument makers have run out of attractive acquisition targets, so they are looking at adjacent businesses, such as diagnostics, which he calls “a diversion.”

The diagnostics business looks good because it’s a big business, Schmid says. Depending on which consultant’s numbers are used, the global market is worth somewhere between $45 billion and $55 billion per year. A report issued in July by Kalorama Information sets the in vitro diagnostics market at $51 billion in 2011 and expects it to grow 5% annually to $64 billion in 2016.

Older, more commoditized diagnostics make up 35% of the dollar value and 65% of the number of tests run, Kalorama reports. Those markets are growing in the low single digits, the consulting firm says. Newer molecular- and genetics-based test markets are growing at double-digit rates.

Physicians rely heavily on diagnostic tests whether old or new, notes Mark Bruns, senior director of clinical operations at Waters Corp., the sixth-largest instrument maker. Such tests provide about 60% of the information a physician uses to make decisions for a patient’s treatment, he says.

Diagnostics account for only about 2% of annual global health care spending, Bruns says. Industry sources set global health care spending at about $2.5 trillion. But given their growing ability to provide more informative answers, improve the quality of health care, and lower overall health care costs, Bruns suggests, diagnostics’ share of health care spending could increase.

Although opportunity is knocking, the big scientific instrument makers are in for a lot of competition, Schmid and Glorikian caution. Contenders include genetic sequencing experts such as Qiagen, Illumina, and Affymetrix, as well as diagnostic businesses tied to big pharmaceutical firms such as Roche, Novartis, and Abbott.

Established diagnostic labs such as Quest Diagnostics also play a role, and medical device companies have entered the in vitro diagnostics space. GE Healthcare, for example, bought cancer diagnostics lab Clarient in 2010 and molecular diagnostics firm SeqWright earlier this year.

In addition, diagnostics have attracted new entrants from the consumer products world. They include Sony, which recently started making microfluidic devices for in vitro diagnostics; Samsung, which has started a cloud-based genome sequencing data analysis service; and Nestlé, which last year bought Prometheus Labs, a developer of diagnostics for gastrointestinal diseases.

What all these companies see in high-tech clinical diagnostics is an opportunity to bring their own expertise to a growth market with a potential for strong profits. Marc N. Caspar, president and chief executive officer of Thermo Fisher, sees just such an opportunity in the acquisition of transplant diagnostics firm One Lambda.

Speaking to analysts during a July earnings conference call, Caspar said One Lambda “will be an excellent addition to our specialty diagnostics portfolio because it will enhance our leadership with strong technologies that generate high margins and create opportunities for long-term growth.” He noted that One Lambda complements Thermo Fisher’s existing immunosuppressant assays for monitoring drugs in transplant patients. Thermo Fisher’s specialty diagnostics business, which now includes Phadia and the Brahms biomarker-based diagnostics business the firm acquired in 2009, is profitable. In the first half of this year, the business unit booked sales of nearly $1.5 billion and an operating income of almost $390 million.

But Thermo Fisher’s specialty diagnostics business didn’t reach its current shape without some earlier reorganization. The firm sold a genetics-based testing business, Athena Diagnostics, to Quest for $740 million in April 2011. A Thermo Fisher spokesman says Athena was “not core” to the firm’s business and that Phadia and One Lambda are more on the technological cutting edge.

David Esposito, U.S. commercial operations vice president of Thermo Fisher’s immunodiagnostics business, says Phadia has thrived under Thermo Fisher. Esposito, who formerly led Phadia’s U.S. operations, says Thermo Fisher has accelerated the Phadia business’s access to emerging markets and invested in its microarray allergy diagnostics technology. He expects Thermo Fisher to similarly invest in One Lambda once it becomes a part of Thermo Fisher.

Agilent likewise has big plans in diagnostics and says the Dako acquisition will establish it as a force to be reckoned with. The firm’s quarterly earnings statement for the period ending July 31 is the first to report diagnostics as a separate business alongside chemical analysis, life sciences, and electronic measurement. Sales for diagnostics were $106 million.

During the May conference call with analysts after the acquisition announcement, Agilent CEO William P. Sullivan pointed to annual growth rates of 8–10% in the $2.2 billion anatomical pathology market, where Dako’s test kits are used. Because more than 90% of Dako’s sales come from reagents and services, the Dako acquisition should increase Agilent’s revenues from consumables from 25% to 30% of the firm’s total sales, he said. More sales of consumables mean Agilent will be less exposed to slowdowns in purchases of capital equipment and more reliant on steady purchases.

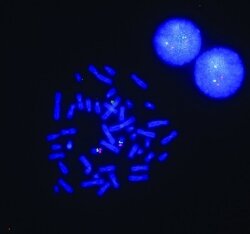

Yet another benefit of the acquisition, according to Sullivan, is that Dako will help Agilent bring to diagnostic labs Agilent’s own fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) technology, used to image chromosomes in cancer diagnostics. That molecular diagnostics market, with global annual sales now at about $4.5 billion, is growing at 10–15% annually, he said.

Robert Schueren, vice president of genomics at Agilent, tells C&EN that Agilent had less than $75 million in annual diagnostics sales before the acquisition, or only about 1% of its overall sales. Dako will boost that figure appreciably.

Dako brings an experienced staff that can help Agilent meet government requirements for clinical tests, Schueren says. The cancer testing firm also is working with drug company partners to develop companion diagnostics for new drugs. Schueren expects that Dako will help Agilent introduce its FISH probes into pharmaceutical companies’ new drug development programs.

Life Technologies says physicians will increasingly come to depend on technology provided by firms such as Navigenics and Pinpoint Diagnostics, its two recent acquisitions. “We see huge potential in the diagnostics market from both a revenue standpoint and the ability to improve human life,” says Ronnie Andrews, president of Life Technologies’ medical sciences business.

“As genome sequencing and other molecular technologies mature, we will see a payoff from our societal investment in biological research,” says Andrews, who was formerly chief executive of Clarient, now owned by GE. The payoff will include the ability to accurately diagnose diseases and use diagnostic information to treat them. It will also include the ability to predict and prevent diseases, he says.

For Life Technologies, diagnostics are a logical extension of existing strengths, Andrews says. The firm is already a major supplier of equipment and consumables that support genetic and proteomic analysis as well as technologies such as PCR, flow cytometry, and immunohistochemistry, he notes.

The firm also has its eye on diagnostic work with pharmaceutical makers. Last October, Life Technologies started a partnership with GlaxoSmithKline to develop a companion diagnostic for a cancer treatment. Andrews says Life Technologies is looking for other such partners. And he says to expect “additional, small, select acquisitions, which, like Navigenics and Pinpoint, will be integrated into our existing diagnostics business.”

For Danaher, the acquisition of Beckman Coulter put it solidly in the clinical diagnostics market. Danaher CEO H. Lawrence Culp Jr. told analysts in an earnings conference that among the first things Danaher did after the purchase was split Beckman Coulter into a diagnostics unit and a life sciences unit “to provide appropriate focus around each of those businesses.”

Danaher’s plan for Beckman, Culp said, includes taking advantage of “strategic synergies in clinical and research applications” between Beckman and other Danaher businesses. They include the Leica Microsystems microscopy business, bioanalytical instrumentation maker Molecular Devices, and mass spectrometry specialist AB Sciex.

Rainer Blair, president of AB Sciex, says businesses such as Leica and Beckman put Danaher “in the middle of the diagnostics space.” And although AB Sciex has been traditionally involved in analytical chemistry, it too is targeting diagnostics.

In February, AB Sciex achieved certification for its manufacturing facility in Singapore and its R&D design center in Toronto as a step toward complying with European regulations to supply instruments for clinical diagnostic use. The firm now sells instruments only for research purposes.

Blair says the firm hopes to supply instruments for the European clinical diagnostics market beginning next year and will enter the U.S. market when it receives FDA approval. Ultimately, the firm hopes to develop diagnostic kits, but details are still under wraps. “By leveraging our mass spectrometry capabilities, we expect to be a leader in the clinical arena,” he says.

In pushing further into diagnostics, other instrument companies are following the lead of PerkinElmer, which has had a stand-alone diagnostics operation for years. The scientific instrument maker has built a business largely focused on prenatal and newborn screening. The business, part of its $887 million human health division, allows PerkinElmer to tap into emerging economies such as China and Brazil, says Jim Corbett, president of the firm’s diagnostics unit.

A simple heel stick with a PerkinElmer kit allows labs to screen newborns’ blood for a large number of genetic and metabolic disorders within 48 hours. Growth in this market is coming from governments that can now afford neonatal testing, Corbett says. In time, he adds, PerkinElmer expects to expand its screening business to children and even adults so physicians can better monitor health and treat disease at the earliest sign of a problem, he says.

Acquisitions have been part of PerkinElmer’s diagnostics expansion strategy and are likely to enlarge the business in the future. About two years ago, the firm bought Sym-Bio Lifescience, a Chinese maker of instruments and reagents to diagnose infectious disease. It also acquired the prenatal and newborn genetic screening business of India’s Surendra Genetic Labs.

Last year, the company bought Caliper Life Sciences, a molecular and tissue imaging expert. Kevin Hrusovsky, former CEO of Caliper and now president of life sciences and technology at PerkinElmer, says Caliper found a solid partner in PerkinElmer to translate to the diagnostics market the molecular screening and genetic profiling technology it had developed.

To extend its franchise in the diagnostics market, PerkinElmer is starting up a Personalized Health Innovation Center of Excellence in Hopkinton, Mass., that will bring together experts from the firm’s chemistry, biochemistry, cell biology, and molecular biology and reagent development teams. Hrusovsky says the center will aid research in early detection of disease, next-generation treatment, and disease prevention.

The mass spectrometry provider behind PerkinElmer’s newborn metabolic screening service is Waters Corp., which also has its eye on the growing diagnostics market. Testing for metabolic disorders in an aging population, as well as the growing incidence of obesity and diabetes, offers significant opportunities for Waters, according to Bruns, the firm’s clinical operations head.

More than a decade ago, advances in genetics and metabolics reinvigorated Waters’ clinical diagnostics and reagents business, Bruns says. In 2007, the firm received FDA approval for its mass spectrometry kit and method to monitor the generic immunosuppressant drug tacrolimus. Bruns says the method is the most accurate way for kidney and liver transplant patients to monitor levels of the drug in their body.

And Waters is focusing on ways to enhance the productivity of its mass spectrometers in the clinical lab. Earlier this year it started working with the Swiss automation equipment maker Tecan to improve preparation of samples for liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry analysis. Bruns says the effort will eliminate manual pipetting of samples and is “intended to address a bottleneck to the adoption of mass spectroscopy in the lab.”

What is exciting about the diagnostics market “is that it is growing, profits can be quite good, and it is not dependent solely on the research market,” says Glorikian, the consultant. Once a test method for a disease is well established, orders for consumables keep rolling in. “Doctors want clinically actionable data,” he says. And technologically driven companies that can give them that data “get the right to play.”

- Chemical & Engineering News

- ISSN 0009-2347

- Copyright © American Chemical Society